Writers use many different digital tools to help them organize, keep track of and otherwise map their novels. The app I hear about the most is Scrivener, but there are many, including Manuskript, which is open source. Whatever the price point, all these apps by definition keep you tied to your devices. Even if you use one of them with good results, I'd like to propose a (mostly) analogue mapping project. A change of mindset is always good for getting perspective. In our digital era, the antidote many contemporary writers need for what ails their works-in-progress is ... paper.

Or even another writing tool. One day a little while ago, I forgot my phone when I went to the dog park. I had nothing to do but watch the dogs, which was fine — in fact it was great, because it got me thinking. Before long, I was sketching in the dirt with a stick, drawing ideas for how to rearrange a book I'm working on. That new interface — the very awkwardness and transience of drawing in the dust — made me simplify my thinking, and I may have solved an important problem.

When we think about the shape of texts, we sometimes lean on familiar narrative structures — the hero's journey, Freytag's pyrmid, etc. (for further notes specifically about various narrative structures, see here) — but just now, the project is to assess the pages you have written so as to more clearly see and be able to foster the latent structures within them.

I'll set the task up by offering two case studies of novels whose structures are innovative and essential to both their readability and their resonance.

CASE 1: Regeneration by Pat Barker

The novel opens with Siegfried Sassoon's open letter in objection to the (First World) War. Later in the first chapter, we are given another text, from a military citation for valor bestowed on Sassoon before his collapse. In between these texts, we get short alternating sections of about a page (or less) from two close-third points of view — that of the central character, Rivers, a psychiatrist, and that of Sassoon, the soldier-poet-shell shock victim. There is much dialogue in Regeneration, and it often drives the story, providing essential information, and yet it manages never to feel expository. As the first chapter, so the novel. It is built of many short sections within longer chapters, with frequent point-of-view changes and many inserted texts. Such quick changes could be wearying, if not carried out so expertly, but Pat Barker always gives just enough material for her readers to sink our teeth into a situation, just enough to trigger our emotional engagement with the situation. Then she rips us away and presents us with another facet of her story. She develops her readers' curiosity with these short scenes and also teaches us (without us ever feeling we're being taught) how the parallel narratives reflect and comment on one another.

CASE 2: The Blind Assassin

This complex novel is one of my favorite books. I sat down one night early on in the pandemic and charted out its patterns, hoping to understand how it was built.

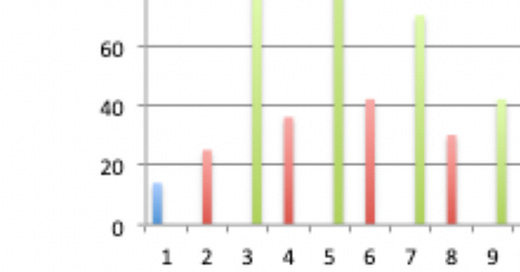

The Blind Assassin is unusual in structure. The chapters can be grouped into three main types: newspaper clippings that document events in the life of Laura Chase, chapters that follow Laura's sister, Iris Chase's story, and excerpts from the eponymous novel-within-the novel, "The Blind Assassin" by Laura Chase. The novel-within-the novel and the clippings have a much larger presence in The Blind Assassin than the found texts in Regeneration. Despite an initial feeling of great textural variety and difference in scale across the three types of section in The Blind Assassin, on closer examination, the unfolding of the sections turns out to be extremely regular. I believe the rhythms underlying the three narrative threads are one of the keys to the book's power.

The three types of narrative are quite diverse and sometimes deliver contradictory content in terms of the facts of the outer story about the Chase family, but they nonetheless cohere and work together. Perhaps the greatest lesson I take from The Blind Assassin is that regular patterns add meaning by teaching readers to compare disparate parts, allowing those parts to accrete meaning and expand the readers' tolerance for dramatic shifts. This regularity paves the way for a story rife with turmoil, tension and conflict. It makes all the messiness both easier to digest and narratively more devastating.

(At the end of this note, you'll find a link to my chapter breakdown including a bar graph that unpacks the shape visually.)

PROMPT: Create a map — or a few maps — of your novel (or story, or memoir or other text).

I think that the best way to map your novel is old school. There are a lot of analog options. I like index cards, color coding, drawing charts and generally drawing various pictures of the shape of the text, with labels for the various parts of sections. When it get's down to the nitty gritty, if there's rearranging to do, it may be worth printing out, chopping your manuscript into bits and laying them all out on the floor or a ping pong table and using tape to rearrange them.

The non-digital mapping I'm suggesting doesn't compete or conflict with any app you may be using. Take all Scrivener or Manuskript's info— if you have it — and use it. Then direct your attention to things that cannot so easily be tracked or detected by these programs. Scrivener and its competitors do not know what happened to you that day in kindergarten that made you love dandelions. Even my favorite of the writing apps, the open-source Manuskript — which has a link to a method for composing a novel based on fractals and snowflakes as structural elements — could not guide a writer to dream up the sort of fractals that structure Toni Morrison's Beloved. There is one digital tool I do like a lot — word clouds — because they throw back out a very analog analysis.

When you set out to assess, map or organize the sprawl of your novel, first think about time. Did the story come out alpha-to-omega chronologically? Probably not completely, but is the main narrative of your novel chronologically linear? Maybe, in which case your time line is simple, but even if it is, is any novel, really completely linear? Almost every work of fiction of any length contains flashbacks. What sort of flashbacks are you using? Longer set pieces or short glimpses, threaded into paragraphs or even into sentences that are set in the present? Possibly both. If both, is there a pattern or a rhythm that governs when your flashbacks are longer and when they are shorter? If there is no rhythm, should there be?

Next, think about the other narrative elements you're working with: points of view, settings, major events, characters, themes, narrative forms like letters, excerpts, or texts. List them, creating a sort of key to a future map, or maps. A map key or legend makes it easier to understand the different elements included on the map, but it also defines the scope of the world by saying what's included. A hiking map uses colors to represent various types of terrain, different sorts of lines to indicate trails, paths and roads, various icons to indicate summits and other landmarks, and contour lines to represent steepness and altitude. It also usually includes a compass rose. What are your story's cardinal points? What are the elements you need to include for your map to usefully represent your text?

Then work your way through your text and chart the point-of-view changes, if you have them. (This could include changes from a younger to an older, wiser version of the same character or narrator, not just changes in individual characters.) Do you alternate? Is there one massive section from one point of view, then another of equal scale? Do you spend the most pages on the most important parts? Would there be value to shuffling and intercutting more often? Or do you change very quickly from person to person and might you slow that down? Then look at your settings in a similar way, and from there, go through each narrative element you've identified and chart it. Maybe scenes alternate between the club in Vegas and the roadside stand in your protagonist's hometown in Kansas, and always in between comes a stop on a road trip. Or, mostly, but there's one road trip stop you skipped. This kind of analysis can help you notice that and decide to add it in, if it would benefit the story. If you can't find a pattern, should there be one, could you put one in?

Rhythms are pleasing to readers because they are predictable (but hopefully not too predictable). They can also help develop suspense. They imbue a sense of meaning through their regularity and variations. You should look for the rhythms you already have and heighten them. However, if rhythms don't appear, or your story structure isn't evident to you by now, this exercise can help you find them.

Ask yourself what is unique to your story. Maybe your text is about baseball or hurricanes, dreams or invasive species or terrorism. Whatever it's about, there are sure to be structures innate to that concept: innings, spirals, shape-shifting, rhizomes, cells whose members remain anonymous but have parallel traumas and grievances... All these things would make great structural schema. Now, whether or not you are a visual artist, you might try to draw it. Use the way the world you're writing about is shaped to help you structure your text.

I recommend doing this by hand. Of course, you can also type it, if that works better for you. But, whatever your medium, make maps that fit onto one page so you can see them in one glance. Perhaps you'll end up drawing dozens of different maps that could represent your novel differently. Make as many as you find useful.

As long as it continues to be illuminating or useful, keep searching for patterns and developing your maps. Once you have a map or maps you like, you can use it to revise the text. Maybe you'll reorganize things in a big way. What if you moved huge sections of text around? Could you create a better or more narratively satisfying structure? As you consider such things, ask yourself: Where is your central conflict introduced? your crisis brought to a peak? your catharsis? Do you have (or need) a catharsis? Maybe there's an inversion or a new beginning at the place we expect that. Where are the moments of greatest energy, anxiety, tension, joy? Are there secondary plot lines? If so, consider their narrative shapes, too. Are there characters or storylines left unresolved? Ends that need to be tied? Or maybe your changes will occur at the granular level. Take whatever the mapping has revealed to you back to your manuscript in any way that works. Maybe you'll plug new ideas about structure, character and theme in to your writing app, or you'll try index cards, Post-its, or a murder board. Have fun with it.

FURTHER READING

Pat Barker, Regeneration, opening

Blind Assassin Analysis by Elizabeth Gaffney